If a happiness index was taken within the last few weeks, it would have shown Tanzanians to be the happiest people in the world, according to some Tanzanians on social media.

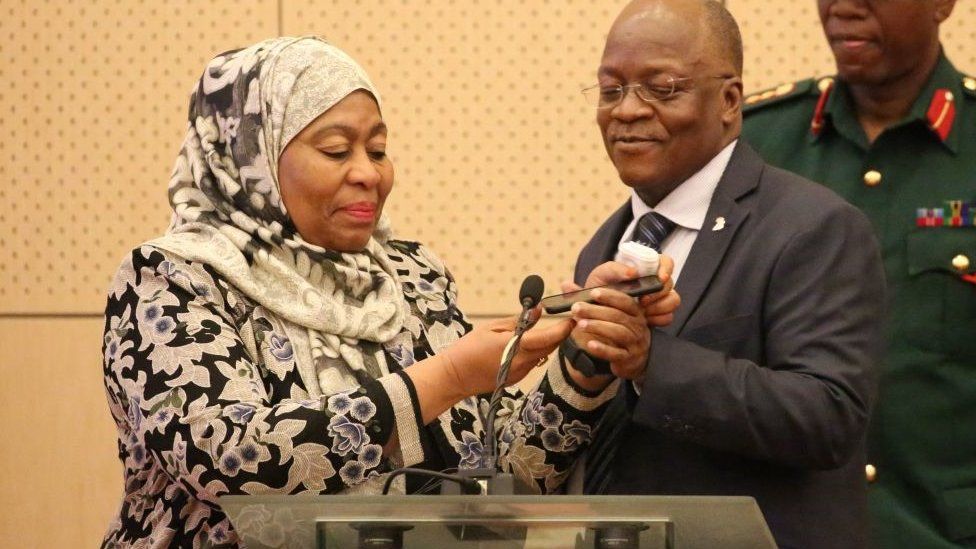

Within the past few weeks, President Samia Suluhu Hassan, widely known as just Mama Samia, met the two leading figures of the opposition party Chadema, Tundu Lissu and Freeman Mbowe – meetings that would have been unimaginable just over a year ago.

Mr Lissu is living in exile after he was shot 16 times in 2017 in an assassination attempt widely believed to have been politically motivated. Mr Mbowe has just been released from jail, where he was held on terrorism charges since his arrest last July ahead of a public rally to demand constitutional reform.

“You should see the smile on my face. Definitely warms the heart. A true leader. Unmatched in her league #ServantLeadership,” tweeted Sara Ezra Teri, hours after news broke of the meeting between President Samia and Mr Lissu in Belgium.

Lawyer and prominent activist Fatma Karume tweeted: “I am PROUD of you, SSH [Samia Suluhu Hassan]. Lissu proud of you too.”Media caption,President Samia: I managed to maintain peace and stability

A year ago, Tanzania was a very different place.

Then-President John Magufuli believed the opposition were puppets of foreign interests. His only language towards the opposition was force, and he made it his mission to eliminate multiparty politics.

That things have changed is agreed across the political divide.

“I’m not a cheerleader, [but] there are things which Mama [Samia] has started to do well. And because she has been doing well, we will support her to do them better,” Mr Lissu said.

What is contested, however, is whether President Samia can take full credit for these changes. Tanzania plunged into authoritarianism under the same ruling party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), that she now chairs.

She was the vice-president in a government that worked hard to eliminate the opposition and sent people to jail for simply criticising it. Many kidnappings and forced disappearances, widely allegedly to be politically motivated, happened under the government where she was second-in-command.

There is also the question of how far is she willing to go to institutionalise the reforms which are currently taking place. Many of them appear to be based merely on the president’s goodwill.

For instance, while meeting opposition politicians is a significant step towards building trust, the controversial Political Parties Act remains unchanged. This gives the registrar of political parties wide and vague powers to de-register parties and hand up to a year in jail to anyone engaging in unauthorised civic education, such as encouraging voter registration.

Likewise, while bans on several media outlets have been lifted, the 2016 Media Services Act, the 2018 Online Content Regulations and the 2015 Cybercrimes Act that enhanced censorship and threatened individuals and media companies with sanctions such as suspension and closure of outlets are still in force.

What President Samia has achieved so far is to put the brakes on a fast descent into total authoritarianism. She has returned the country to the pre-2015 era, but has done little to alter the institutional structures which enabled her predecessor to crack down on dissent so completely.

These moves towards a more tolerant type of politics suggest that the president wants to make changes. But her actions hint that she is torn between pursuing reforms and keeping the party she leads in power. For example, the opposition politicians she has met still face restrictions if they want to hold rallies.

However, there is a sense that these changes will last. This optimism is drawn from the belief that President Samia has now fully consolidated her grip on the ruling party.

In the first few months after Mr Magufuli’s death, she had to remind her audience that as a female president she was still worthy of respect and trust. Back then, ministers tended to only partly carry out her directives.

Her growing authority is probably best illustrated by the release of Mr Mbowe – whose prosecution was pursued for eight months despite a lack of evidence and widespread calls to drop the case.

It is believed it was dropped in the end because she stood up to some remaining Magufuli loyalists who resisted some of her reforms.

Some liken the ongoing changes to the era of former President Jakaya Kikwete, who was one of Mrs Samia’s mentors and Mr Magufuli’s predecessor.

His leadership style was conciliatory, and political differences with the opposition were often resolved through dialogue over a cup of tea and nibbles at state house. As a result, the government tended not to enforce repressive laws.

This impression is backed by the return of the so-called liberal economic policies. Foreign investors are being actively wooed, Western donors are now regarded as development partners as opposed to imperialists or “mabeberu”, loosely translated as male goats – a disparaging term used by Mr Magufuli.

With her roots in collaborative activism and growing up in Zanzibar, where there is a culture of humility and hospitality, it is not surprising she has a different leadership style.

But she could face significant resistance from the CCM if she, for example, agreed to a referendum on constitutional reforms, a long-standing demand of the opposition and pro-democracy activists, as it could disadvantage her party by loosening its absolute grip on power.

President Samia took office in extraordinary circumstances, in a country and political system dominated by patriarchal attitudes which were promoted by her predecessor.

In one public address, former President Magufuli jokingly fantasised about beating up resistant women, while in an other he made sexual remarks about a Member of Parliament over her light skin. He received applause on both occasions.

One year later, President Samia has succeeded in reviving hopes of a fresh start.

However, the true measure of her intent to make lasting changes lies in the speed and extent of legal and institutional reforms which would not only cement her legacy but also protect Tanzanians’ freedoms, and shield the country from potential authoritarian leaders who reach State House in future.

Source: BBC