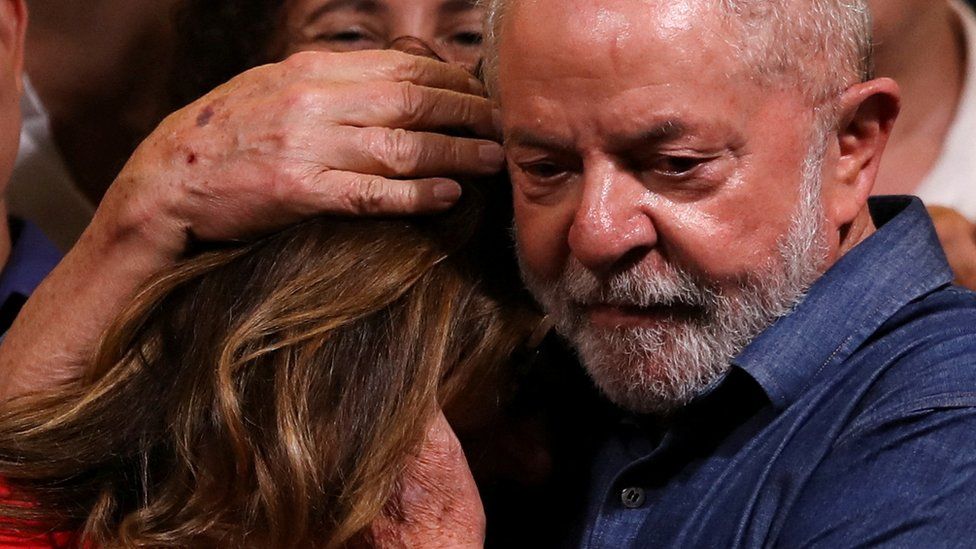

Brazil has taken a turn to the left as former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva beat far-right incumbent Jair Bolsonaro in the presidential election.

After a divisive campaign which saw two bitter rivals on opposite sides of the political spectrum go head to head, Lula won 50.9% of the votes.

It was enough to beat Jair Bolsonaro, whose supporters had been confident of victory.

But the division which this election has highlighted is unlikely to vanish.

It is a stunning comeback for a politician who could not run in the last presidential election in 2018 because he was in jail and banned from standing for office.

He had been found guilty of receiving a bribe from a Brazilian construction firm in return for contracts with Brazil’s state oil company Petrobras.

Lula spent 580 days in jail before his conviction was annulled and he returned to the political fray.

“They tried to bury me alive and here I am,” he said, kicking off his victory speech.

Five key facts about Lula

- 77 years old

- Left-wing

- Former metal worker

- President from 2003-2010

- Imprisoned in 2018 but conviction was later thrown out

Opinion polls suggested from the start that he would win the election, but when his lead in the first round was much narrower than predicted, many Brazilians started to doubt their accuracy.

Jair Bolsonaro’s backers – encouraged by their candidate’s allegations that “the establishment” and the media were against him and therefore underplaying his support – had complete faith in his victory.

The left-wing leaders victory is likely to rankle with these Bolsonaro fans, who routinely label Lula “a thief” and argue that the annulment of his conviction does not mean he was innocent, just that the proper legal procedure was not followed.

And while Jair Bolsonaro has lost, lawmakers close to him won a majority in Congress, which means that Lula will face stiff opposition to his policies in the legislative body.

But Lula, who served two terms in office between January 2003 and December 2010, is no stranger to forging political alliances.

As his vice-presidential running mate he chose former rival Geraldo Alckmin, who ran against Lula in previous elections.

His strategy of creating a “unity” ticket seems to have paid off and drawn voters into the fold who may not have consider otherwise casting a ballot for his Workers’ Party.

In his victory speech, he struck a conciliatory tone, saying he would govern for all Brazilians and not just those who voted for him.

“This country needs peace and unity. This population doesn’t want to fight anymore,” he said.

Jair Bolsonaro has yet to concede. The campaign had in part been so tense because the far-right president had cast doubts – without offering any evidence – on the reliability of Brazil’s electronic voting system.

This fomented fears he might not accept the result if it went against him.

A day before the second round however, he stated that: “There is not the slightest doubt. Whoever has more votes, takes it [the election]. That’s what democracy is about.”

Five key facts about Bolsonaro

- 67 years old

- Far-right

- Former army captain

- Running for a second consecutive term

- Has cast unsubstantiated doubts on the trustworthiness of Brazil’s electronic voting system

On election day itself, busses carrying voters to the polls were stopped by police in what Lula’s campaign said was an attempt to prevent them from voting.

The head of the electoral court, Alexandre de Moraes, ordered the highway police to lift all roadblocks and checks.

He said that while some voters had been delayed, none had been prevented from voting. But the incidents raised tensions considerably.

Now there is much expectation as to when and what Mr Bolsonaro will say now that it is official that fewer votes were cast for him than for Lula.

The election has not just been closely watched in Brazil, but also abroad, with environmental activists in particular worried that another four years of a Bolsonaro government would have led to further deforestation in the Amazon rainforest.

Lula referred to these fears in his victory speech saying that he was “open to international co-operation to protect the Amazon”.

“Today we tell the world that Brazil is back. It is too big to be banished to this sad role of global pariah,” he added in a dig at his rival.

But at the heart of his speech was a promise to tackle hunger, which has been on the rise in Brazil and which is affecting more than 33 million.

Key to Lula’s popularity during his first two terms in office was lifting millions of Brazilians out of poverty.

But in a post-pandemic economy, finding the finances to recreate that feat will not be an easy task, especially if he is hampered by a hostile Congress.