The world must cut greenhouse gas emissions by at least a quarter before the end of this decade to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Progress needed toward such a major shift will inevitably impose short-term economic costs, though these are dwarfed by the innumerable long-term benefits of slowing climate change.

In our latest World Economic Outlook, we estimate the near-term impact of different climate mitigation policies on output and inflation. If the right measures are implemented immediately and phased in over the next eight years, the costs will be small. However, if the transition to renewables is delayed, the costs will be much greater.

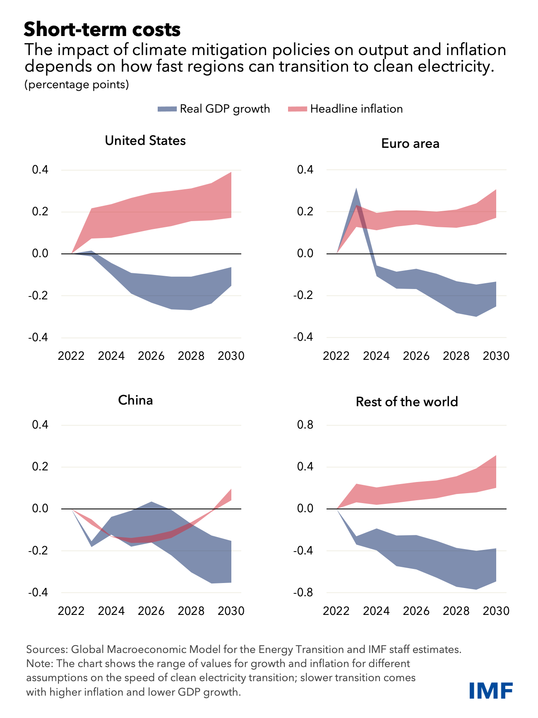

To assess the short-term impact of transitioning to renewables, we developed a model that splits countries into four regions—China, the euro area, the United States, and a block representing the rest of the world.

We assume that each region introduces budget-neutral policies that include greenhouse gas taxes, which are increased gradually to achieve a 25 percent reduction in emissions by 2030, combined with transfers to households, subsidies to low-emitting technologies, and labor tax cuts.

The results show that such a policy package could slow global economic growth by 0.15 percentage point to 0.25 percentage point annually from now until 2030, depending on how quickly regions can wean off fossil fuels for electricity generation.

The more difficult the transition to clean electricity, the greater the greenhouse gas tax increase or equivalent regulations needed to incentivize change—and the larger the macroeconomic costs in terms of lost output and higher inflation.

For Europe, the United States, and China, the costs will likely be lower, ranging between 0.05 percentage point and 0.20 percentage point on average over eight years. Not surprisingly, the costs will be highest for fossil-fuel exporters and energy-intensive emerging market economies, which on balance drive the results for the rest of the world.

That means countries must cooperate more on finance and technology needed to reduce costs—and share more of the required know-how—especially when it comes to low-income countries. In all cases, however, policymakers should consider potential long-term output losses from unchecked climate change, which could be orders of magnitude larger according to some estimates.

In most regions, inflation increases moderately, from 0.1 percentage point to 0.4 percentage point.

To curb the costs, climate policies must be gradual. But to be most effective, they also need to be credible. If climate policies are only partially credible, firms and households will not consider future tax increases when planning investment decisions.

This will slow the transition (less investment in thermal insulation and heating, low-emitting technologies, etc.), requiring more stringent policies to reach the same decarbonization goal.

Inflation would be higher and gross domestic product growth lower by the end of the decade as a result. We estimate that only partially credible policies could almost double the cost of transitioning to renewables by 2030.

Inflation and monetary policy

A pressing concern among policymakers is whether climate policy could complicate the job of central banks, and potentially stoke wage-price spirals in the current high-inflation environment. Our analysis shows this is not the case.

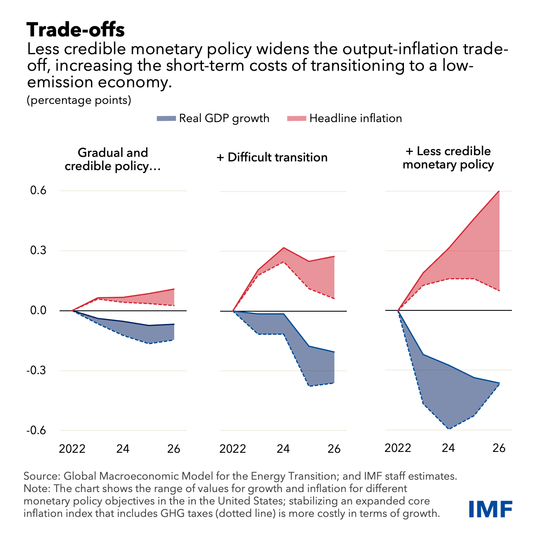

Gradual and credibly implemented climate mitigation policies give households and firms the motive and time to transition toward a low-emission economy.

Monetary policy will need to adjust to ensure inflation expectations remain anchored, but for the kind of policies simulated, the costs are small and much easier for central banks to handle than typical supply shocks that cause a sudden surge in energy prices.

Using the United States as an example, we show how climate policies impact inflation and growth under a range of scenarios. When policies are gradual and credible, the output-inflation trade-off is small. Central banks can choose to either stabilize a price index that includes greenhouse gas taxes or let the tax fully pass through prices. The former would only cost an additional 0.1 percentage point of growth annually.

If the transition is more difficult—reflecting a slower transition to clean electricity generation—the trade-off increases but remains manageable.

The costs would be much higher if monetary policy were to lose credibility, a concern in today’s high-inflation environment. If inflation expectations become de-anchored, introducing climate policies could lead to second-round effects and a larger output-inflation trade-off, as illustrated by the less-credible monetary policy scenario. Our analytical chapter shows how to design climate policies to avoid such a situation, curbing the impact of the greenhouse gas tax on inflation with subsidies, feebates or labor tax cuts.

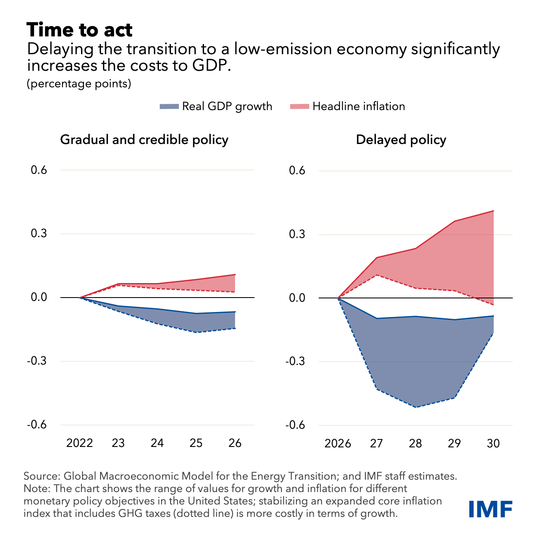

Is it reasonable to wait—as some have proposed—until inflation is down before implementing climate mitigation policies? We ran a scenario delaying implementation until 2027 that still achieves the same reduction in cumulative emissions in the long term. The delayed package is phased in more rapidly and requires a higher greenhouse gas tax, since a steeper decline in emissions is necessary to offset the accumulation of emissions from 2023 to 2026.

The results are striking. Even in the most favorable circumstances when monetary policy is credible and the transition to decarbonized electricity is rapid, the output-inflation trade-off would rise significantly; GDP would have to drop by 1.5 percent below baseline over four years to drive inflation back to target. Delay beyond 2027 would require an even more rushed transition in which inflation can be contained only at significant cost to real GDP. The longer we wait, the worse the trade-off.

Better understanding the near-term macroeconomic implications of climate policies and their interaction with other policies is crucial to enhance their design. Transitioning to a cleaner economy entails short-term costs, but delaying will be far costlier.