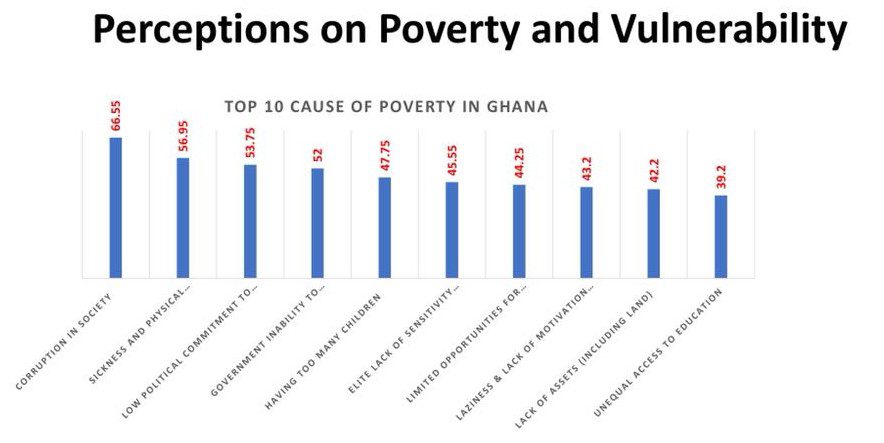

Nearly 67% of Ghanaians have identified corruption as the leading cause of poverty in the country.

This is the outcome of a study conducted by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

Among the top ten (10) causes of poverty, corruption in society was first (66.55%), followed by sickness (56.95%), and low political commitment (53.75%).

Some 52% of Ghanaians say they are poor due to government’s inability to tackle the menace, while 47.75% believe they are poverty-stricken because they have too many children.

The study was conducted in six (6) districts, two each from the Greater Accra, Oti, and Upper West regions of Ghana with a total of 640 respondents, including 58% females.

In Ghana, it is perceived that poverty is prevalent largely in rural areas where most low-income families depend on peasant farming and other minor jobs to make a living.

In the urban settings, access to social infrastructure, including education and healthcare have been noted as some of the factors accounting for poverty.

The UNICEF report reveals that severely disabled persons (78.7%), homeless people or street children (75.2%), and orphaned children (73.8%) are ‘very likely’ to be vulnerable and poor due to factors such as absence and lack of food, clothing and shelter.

These people may also be vulnerable over “a state of helplessness or inability to fulfill needs without external support.”

A 2019 World Bank report on Ghana’s poverty and equity distribution showed that “Ghana’s largest fall in poverty was experienced from 1991 to 1998. Since then, poverty reduction has slowed down, and the growth elasticity of poverty has decreased remarkably.”

“The extreme poverty rate declined from 5.2 percent to a negligible share in Greater Accra between 2005 and 2016, while the extreme poverty rate fell from 76 percent to only 45.2 percent in Upper West region during the same period,” the data indicated.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) is suggesting that rights-based objectives should be integral to design and implementation of social protection programmes.

It adds that the one-size-fits-all approach to dealing with poverty and vulnerability must be avoided to ensure that access to water and sanitation, health and education are evenly distributed among rural and urban people.

Key informant interviews were conducted at the national, regional and district levels with media practitioners, donors,

Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), senior policy makers, religious leaders, district social welfare officers, among others.